LETTER | It was a timely decision for Education Minister Dr Maszlee Malik to appoint Permatang Pauh MP Nurul Izzah Anwar as the chairperson for a newly formed Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Empowerment Committee.

So far, TVET in Malaysia has been given much less attention than mainstream academic education system. It has been run under seven ministries – the Education, Higher Education, Human Resources, Public Works, Agriculture and Agro-based Industries, Rural and Regional Development, and Youth and Sports Ministries.

There have been so many ministries involved in TVET, with an allocation of RM 4.9 billion in 2018 for the TVET Master Plan, but merely seven percent of school leavers eventually join TVET programmes.

There is an undersupply in 10 out of 12 key economic areas, while only 70 percent of vacancies in TVET are being filled up.

It is acknowledged that there has been a severe lack of coordination between the respective ministries and departments whose functions are overlapping, and some are redundant.

Streamlining TVET

There is a study underway by the Human Resources and Economic Affairs Ministries to combine all TVET into a single agency and a single ministry. TVET should be an integrated part of the education system where education is to nurture productive and competitive workforce.

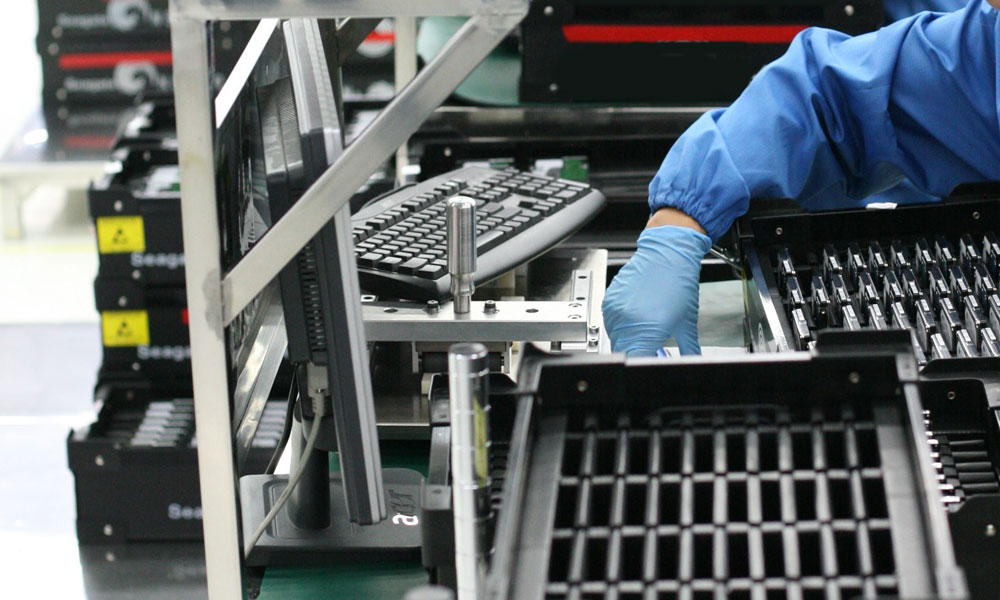

This is certainly a wise and timely move to elevate the country’s economy effectively towards industrial revolution 4.0 through an effective education system. The combination of automated assembly line, the internet of things and artificial intelligence, requires highly-skilled workers highly proficient in ICT. It will also lessen our dependency on labour, especially migrant workers, while elevating our workers’ competitiveness and earning powers.

Even though there has been a positive decrease of up to 75 percent in the dropout rate from the year 2000 to 2013, youth (15 to 24) unemployment rate remains high compared to other age groups. Even if they are employed, whether they possess adequate skills affects their level of income and self-esteem.

According to Education Ministry statistics, the number of students who dropped out before completing their primary education was 3,920 students in 2013, or one percent of the total primary school student population. The number of those who do not continue to finish their secondary school is 14,396 or three percent of the student population.

In other words, we have about 20,000 non-skilled youth entering the job market, who are at worst unemployed or at best get to work as non-skilled workers at the lowest wage spectrum.

According to a Statistics Department survey in 2015, when the national unemployment figure was at 3.1 percent, the unemployment rate among youths was about 10.7 percent (15. percent for the age group 15-19; 9.3 percent for the age group 20-24) ,which is three times the national average, or make 60.8 percent of the total unemployed workforce.

This is due to their lack of education attainment, work experience and vocational skills.

Better opportunities

In 2015, of the 405,000 youths with tertiary education, 24 percent were unemployed six months after their graduation, as compared to the fact that only 9.8 percent out of 2.162 million youths without tertiary education were unemployed. 54 percent of graduates who were employed earned less than RM 2,000 a month.

On the other hand, the starting salary of vocational and technical graduates at between RM 2,000 and RM 5,000 a month is even slightly higher than university graduates. 90 percent of TVET graduates (technical and vocational education and training) are employed within a year after their graduation, and their unemployment rate is lower than the university graduates’.

Two questions have been raised as to whether what university graduates learn are mostly irresponsive to demands of the job market, and hence leads to a higher unemployment rate among them, and whether workers without tertiary education do not have quality jobs and wages to lift up their standards of living.

Besides the importance of academic and civic requirements, our education has to be more demand-driven and socially oriented. A high degree of social partnership between public and private sectors has to be sought if tertiary education is made relevant to the socioeconomic development.

Despite these facts, only eight percent of our secondary students are in TVET, which is low compared to advanced countries like Germany and Switzerland, where almost 60 percent of their students are in TVET. In Singapore, as much as 75 percent of secondary students end up in TVET, and only a minor fraction (25 percent) end up in universities.

More importantly, Singapore has geared its country for Industry 4.0 for decades. Accordingly, as a vital strategy to always stay ahead of its neighbours in order to maintain its economic relevance and competitiveness in the world economy, Singapore has long undergone a meticulous pathway charted for Industry 4.0.

According to International Federation of Robotics Report 2017, Singapore is currently ranked number 2 in the world in terms of robotic density –that is, 488 industrial robotic arms per 10,000 workers according to the International Federation of Robotics.

Like Germany, Singaporeans could start TVET as early as lower secondary school, and TVET students could eventually converge into tertiary education in an education system that advocates learning process as a life-long matter. TVET has even been a debatable issue in Singapore to be started as early as the upper primary school level.

TVET qualifications are made as equivalent as academic qualifications in South Korea. Its marketability depends heavily on the demands of the job market, especially since South Korea has been the world number 1 since 2010 for the highest industrial robotic density-that is, 631 robotic arms per 10,000 workers, reflecting its leading role in industry 4.0.

According to Bank Negara’s Economic Development Report 2017, Malaysia has an industrial robotic density of only 34 per 10,000 workers that is even lower than the Asian average of 63 per 10,000 workers, and our industrial robot density is only five percent that of South Korea’s.

Race to the bottom

There are significantly adverse trends in the country’s economic development which is heading for a more regressive labour-intensive and migrant-worker-dependence direction at the expense of the local workers’ competitiveness, productivity and earning capacity.

Firstly, in the last 15 years, the high skilled jobs’ ratio has decreased from 45 percent to 37 percent while low skilled jobs’ ratio has increased from 8 percent to 16 percent. Secondly, the most alarming trend is that 81.5 percent out of the new jobs created have gone to the foreigners, while university graduates unemployment rate has gone up yearly. There has apparently been a mismatch between the education system and the job market.

To solve the adversity in our future economic development, we need a paradigm shift from the conventional labour-intensive and migrant worker-dependent economy to a newly high-skilled and digital-proficient local workforce. The answer to it is the dire need for a highly ICT-digital-proficiency oriented TVET system.

Even though only 9.43 percent of South Korean secondary students take up vocational courses, its tertiary education enrolment rate is as high as 93.18 percent, of which 22.82 percent students engaged in vocational education at the tertiary level. Moreover, 90 percent of South Koran youth commanded a minimal level of digital literacy.

In Germany, apprenticeships in TVET, starting as early as upper secondary school at age 15, expose the apprentices to real industrial working situations. Being protected by a youth employment legislations, apprentices spend 70 percent working in real industries with paid wages and 30 percent in formal classroom education. Almost all German TVET apprentices would be re-hired by their original industries after completion of their apprenticeship.

The close social partnership between TVET institutes, public sector, private individual industries, and the relevant chambers of commerce and guilds play a vital role to make it an effective mechanism for TVET in the 4th Industrial Revolution.

Industry 4.0 involves not only automation and big data exchange in manufacturing technologies, but also includes cyber-physical systems, the internet of things, cloud computing and cognitive computing. It requires not only high skilled workers, but also a workforce with high ICT and digital proficiency.

Therefore, TVET has to be made first choice for some best students, revamping the traditional thinking of TVET as merely the choice for less capable students and academic drop-outs, in order to meet future societal and technology challenges.

The role of industry

Complaints have also been made by TVET educators themselves that Malaysian graduates do not get the deserved wages and job opportunities. This requires an open attitude from educators, and the relevant ministries and TVET institutes to work closely with private industrialists, chambers of commerce and guilds who keep afresh with the latest industrial development and market demands all the time.

Industries have to be made more willing to provide early starting point for apprenticeship as social partners or stakeholders in the process of upscale our TVET as the essential preparation for industry 4.0.

The TVET Committee is vital in institutionalise coordination between too many federal ministries undertaking TVET with the private sector and relevant guilds. For the TVET Committee to be more effective, its chairperson could be upgraded to the level of a cabinet co-minister, who coordinates all ministries, state governments, private industrialists, civil society involved in TVET and streamlines all forms of TVET and their accreditations.

Many public TVET institutions have become underutilised or unutilised where buildings are built and left astray. TVET has to be planned according to the socioeconomic demands.

Franchises of public institutions certification to non-profitable industry guilds initiated training programs are feasible to maximise utilisation of public funding and facilities. This social partnership and franchising of TVET programs is termed as “socialisation” of our education system.

Nonetheless, promoting TVET in industry 4.0 involves “democraticisation” of our education system by which the federal government needs to decentralise and share powers of administering education system including TVET with state and local governments, who know the local demands better.

State and local governments could coordinate between the chambers of commerce, guilds of various artisanship with our education system especially TVET institutes, which in turn has to be tailored according to a tripartite relation between international trends, national aspirations and local demands.

On the other hand, local industries already provide existent machineries and facilities for apprenticeship while the institutes could cut down its expenditures on setting up, but concentrating on teaching theories to the apprentices and training the trainers about on-job teaching.

TVET for Industry 4.0 forces us to review seriously about how our industries would run. While there is a high number of illegal foreign workers (1.7 million) and a marked proportion of semi-skilled local workforce, about half (54 percent) of female productive-age population actually work.

The currently inactive but potential women workforce well surpasses the number of foreign workers and could fulfil the need of our job market. The solution is to provide more welfares such as nurseries and on-job TVET.

The solution to stagnant economic performance and over-dependence on foreign workers is to “socialise” and “democraticise” our education system including targeting 60 percent youth in TVET, of which 40 percent would be female as in advanced countries like in Germany, South Korea and Taiwan, in order to achieve not only a targeted 80 percent women to be in the national workforce, but also be as competitive as their male counterparts.

The issue is not only about TVET alone. but the powers-that-be need to revamp their own perception of what ‘education’ means, which has been conventionally interpreted as the major tool to maintain the social status quo and train the future generation to be living ‘robots’ listening to the commands of their ‘owners’ – and, in recent decades, for cronyists close to them as a means to get kickbacks from construction projects of TVET institutes – than the noble intention to making our workforce prepared for the new challenge of Industry 4.0.

To promote TVET, we have to begin with reshaping our perception and policy towards education, which is not a privilege for some to profiteer, but as a birthright for all Malaysians to be equitably competitive, regardless of gender, race, religion and creeds, in an increasingly challenging world economy.

DR BOO CHENG HAU is the former state assemblyperson for Skudai.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini (source of article)