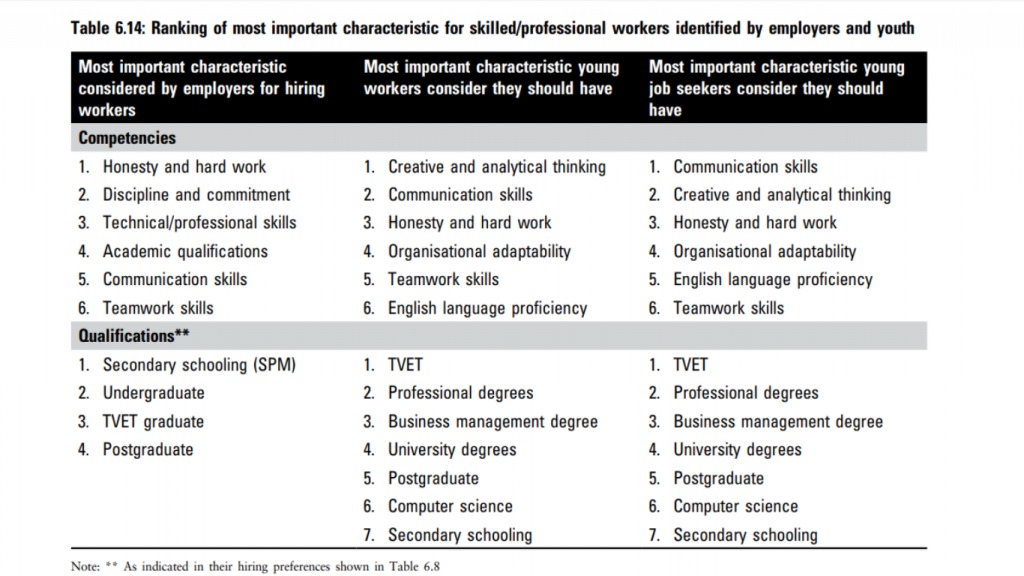

A key aspect of the skills mismatch is between academic qualifications and technical and vocational qualifications. Malaysia’s Education Blueprints emphasise technical and vocational education and training (TVET) as essential for the needs of the labour market and economy. However, only 13% of all upper secondary students are pursuing TVET courses, while at the higher education level less than 9% are in polytechnics. It has often been noted that students and their parents regard TVET as an inferior educational pathway, ‘dead end’ and for the academically challenged. But, in fact, according to the School to Work Transition Survey (SWTS), both young job seekers and young workers consider TVET as the most useful qualification for getting a good job—the reasons for the mismatch/misperception need to be addressed. For example, the salary differential could be an important reason; the SWTS found that there is a significant wage differential between TVET graduates and those with other types of hard skills.

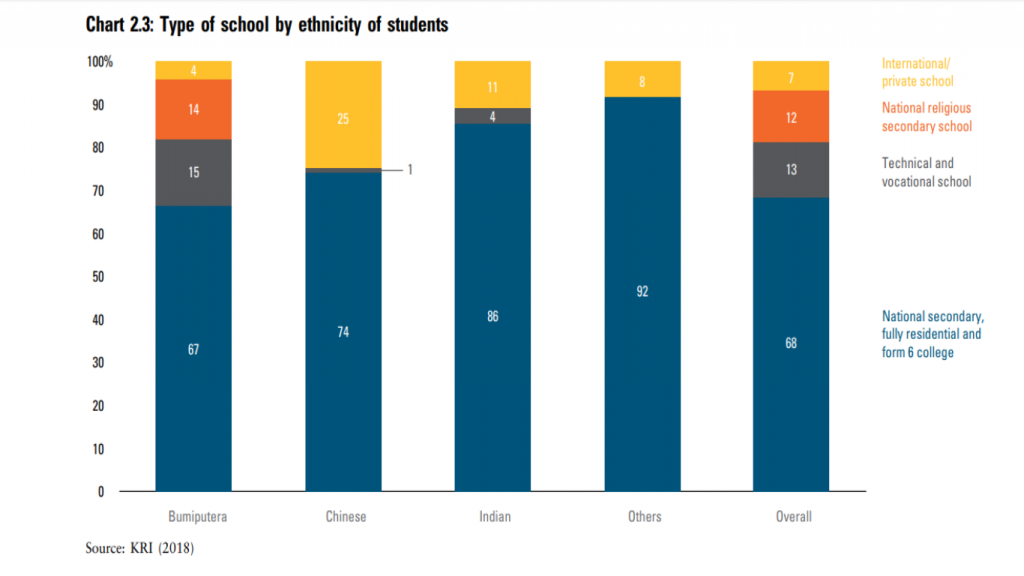

Only 1% of all Chinese and 4% of Indian secondary school students are pursuing technical and vocational education as compared to 15% of Bumiputera students. Despite the government’s recognition of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) as critical to meet the demands of industry and contribute to economic growth, TVET is still not attractive as an education pathway choice. A number of reasons have been identified, including the fact that TVET graduates and practitioners are not recognised as professionals and, therefore are not able to demand higher wages and career advancement. Those from such schools also have limited access to higher education institutions (EPU (n.d., pp.9-4 to 9-7). TVET is often negatively perceived as the second or last choice and only ventured into by those who do not have good academic qualifications (Cheong and Lee (2016)).

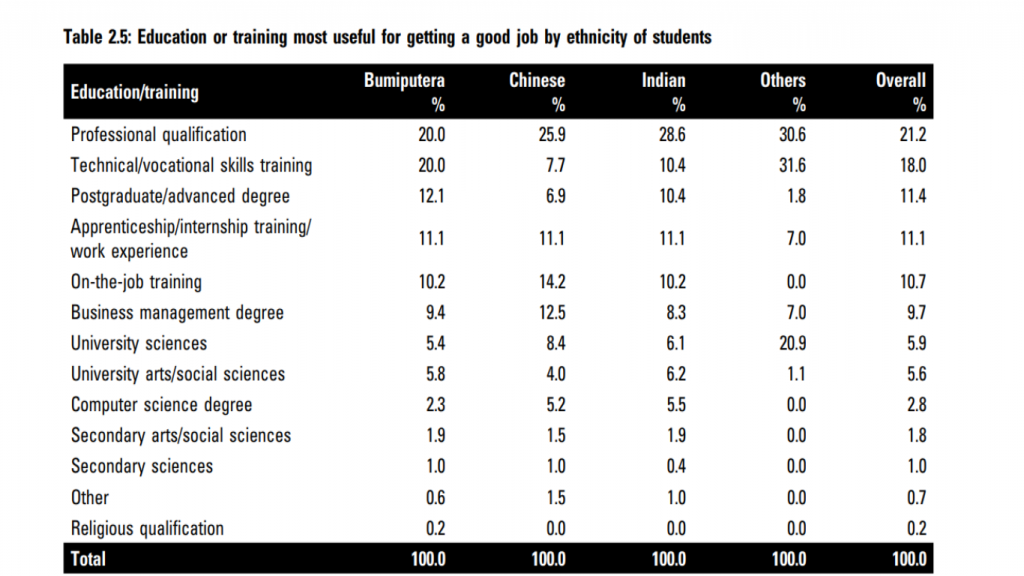

To get a good job, the most useful qualification is professional… The students were asked about the education or training they consider most useful for getting a good job (Table 2.5).

All students, irrespective of ethnicity, gender or urban-rural location, prioritise professional qualifications. This view is clearly in line with their strong preference for professional occupations.

Overall, technical and vocational skills training is the next most important qualification, after professional qualification, to get a good job – this is striking in that it contrasts sharply with the relatively low attendance in TVET schools noted in Chart 2.3.

The secondary school students appear to be aware of the importance of TVET for the job market but would rather pursue an academic education. Chinese students do not find technical and vocational skills training to be particularly important (this may be linked to their relatively low attendance at TVET schools); they put more emphasis on internships and on-the-job training and also on business management degrees. In fact, all ethnic groups recognise the importance of apprenticeship training and work experience for getting a good job. This very likely reflects their perception that employers want to hire those with work experience and that a major reason why they do not easily get jobs upon completing their education is that they do not have practical experience.

Malaysian youth can pursue an academic pathway to acquire a higher education qualification or they have the option of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes that lead to the award of skills qualification (at certificate-Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia, diploma-Diploma Kemahiran Malaysia or advanced diploma-Diploma Lanjutan Kemahiran Malaysia levels). The TVET programmes are currently offered by various ministries, government agencies and private sector institutions, leading to unintended competition and duplication (MOE (2015, p.4-4)). Currently, there is a perception that TVET qualifications offer fewer attractive career and academic progression, thereby limiting the number of students who apply for such courses. The aim of the government, therefore, is to “move from a higher education system with a primary focus on university education as the sole pathway to success, to one where academic and TVET pathways are equally valued and cultivated” (Ibid., p.E-13. In addition, a TVET Masterplan is currently under study to develop skilled talent to meet the growing and changing demands of industry, promote individual opportunities for career development and ensure that the country has the skilled technical workforce it needs to reach high income status)

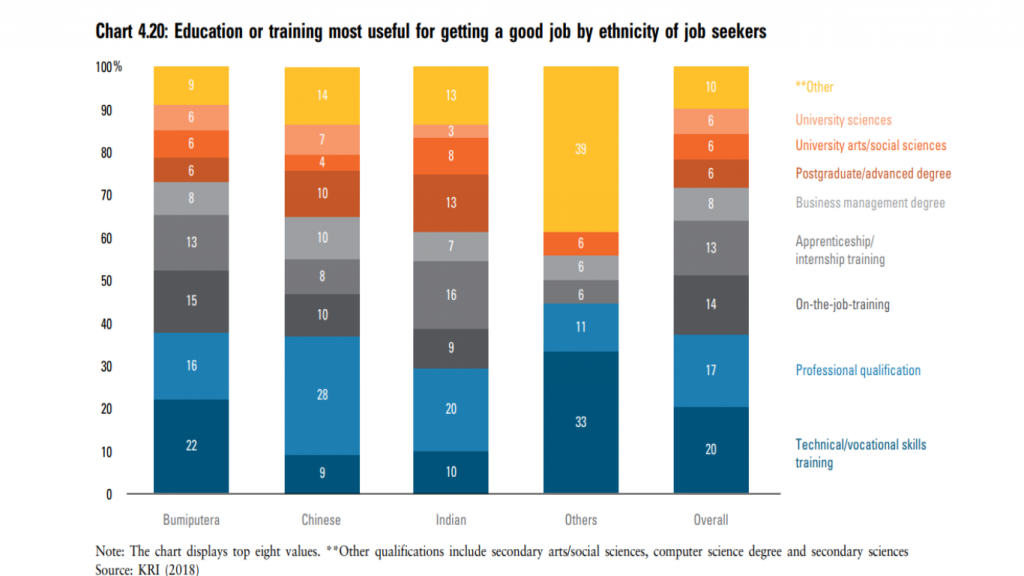

To get a good job, they consider TVET the most useful qualification… The job seekers, in particular the Bumiputeras and Others, identify TVET as most useful for getting a good job (Chart 4.20). This is striking when contrasted with the low ranking given to TVET by tertiary students (20% of job seekers as compared to 12% of tertiary students). It is also striking given that less than 5% of the job seekers have such qualifications (as shown earlier in Chart 4.3). The Chinese and Indian job seekers, on the other hand, feel that a professional qualification is most useful. Among all job seekers there is recognition of the usefulness of on-the-job training and apprenticeships; they recognise that work experience often counts in getting a job.

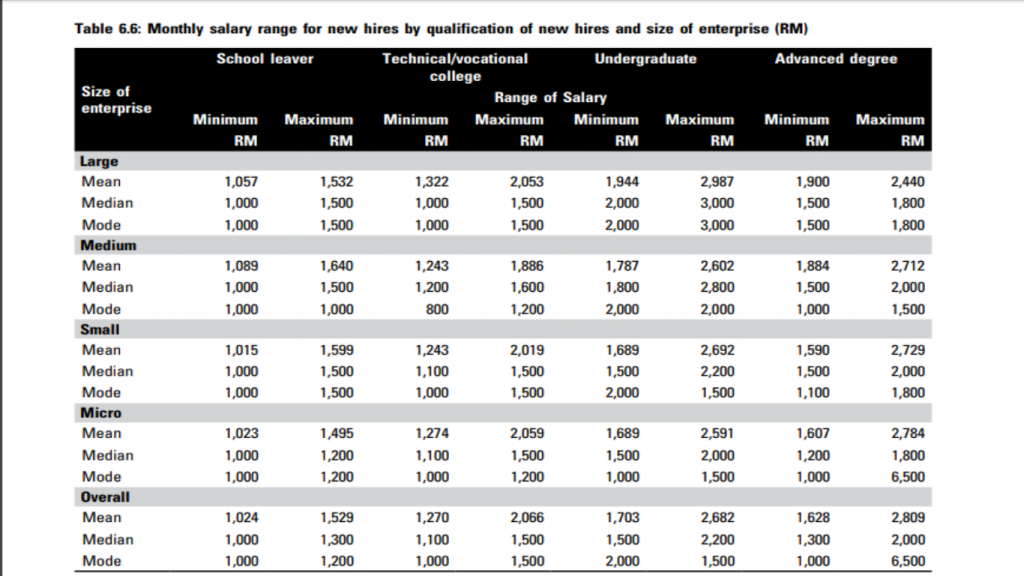

The salary range for new workers

Mean salaries offered for those with TVET qualifications are quite significantly below those for university graduates—which may help to shed light on why TVET qualifications are not popular among the young.

Employers from the public sector, public listed companies and also private contractors prefer undergraduates from local universities for skilled jobs. Other employers who indicate a preference for TVET graduates in skilled jobs include sole proprietors, private limited companies and especially private contractors. For the low-skilled or manual workers, employers do not have strong educational preferences; where there are preferences it is worth noting that the public sector and public listed companies indicate a preference for TVET graduates.

Overhaul the current TVET system

A plethora of weaknesses has been identified in the current TVET system and solutions proposed with little sustainable impact to date. The establishment by the government of a National Taskforce to reform TVET holds promise of real change—that will happen only if there is a complete structural overhaul of the system to:

– Ensure strategic coordination, importantly, by bringing the diverse and huge number of training providers (over 1,000 public and private TVET institutions) under a single effective governance body that can provide quality assurance for the skill outputs from the different institutions;

– Prioritise a demand-driven approach by ensuring close industry involvement to realistically relate training to workforce needs, including providing incentives for employers to offer WBT;

– Establish a relevant and reliable competency standards and qualifications framework for better matching and to facilitate entry of TVET graduates into universities; and

– Raise the status of TVET, including through gender-sensitive labour market information and career guidance, including introducing role models. A review of salary differentials between TVET graduates and those from other educational streams could also shed light on the issues that need to be addressed.

Source: Excerpts from Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) 2018

THERE is something that ails in the way we deliver our technical and vocational education and training (TVET). Experts say that for a country to be a developed nation, it must arm its human capital with the skills that are needed by industry. But TVET seems to be less loved than it should be.

THERE is something that ails in the way we deliver our technical and vocational education and training (TVET). Experts say that for a country to be a developed nation, it must arm its human capital with the skills that are needed by industry. But TVET seems to be less loved than it should be.